When it comes to investing the general belief is liquidity is a good thing. But is liquidity always a positive? The answer is no.

Fifty years of personal investing experience and as many years observing other investors, particularly those managing their own investments, have led me to conclude that too much liquidity has, in fact, done individual investors more harm than good.

Liquidity with a specific purpose in mind is usually positive. For example, there is a clear benefit to having ready access to cash in an emergency fund to cover unexpected medical costs or your expenses between jobs. Other limited benefits of liquidity for the average investor might include keeping money for a down payment on a car or home.

But for most individuals, excess liquidity means time out of the market, which history has shown to be a costly mistake. Cash on hand can present a temptation to impulsively invest when you probably should not. Moreover, many major purchases can be planned for ahead of time, and therefore do not require keeping cash on hand to pay for them. Instead, you should consider other options to raise the money as needed, such as bank loans or mortgages.

Too Much Liquidity is Bad

History shows stock markets rise over the long term, and therefore getting out of the market is betting against this powerful upward trend. The record for market timing is clear: Nobody has been consistently right about when to get out of the market and when to get back in (please see Investors’ Most Serious Mistake).

Using liquidity to move in and out of mutual funds hurts too. Data from DALBAR shows that investors in mutual funds significantly underperform in the very mutual funds they invest in. Why? Because they tend to buy into the funds after the funds have shown good performance and tend to sell after disappointing performance. In general, these costs are estimated to amount to one-third of the potential returns individual investors could, and should, be getting on their investments.

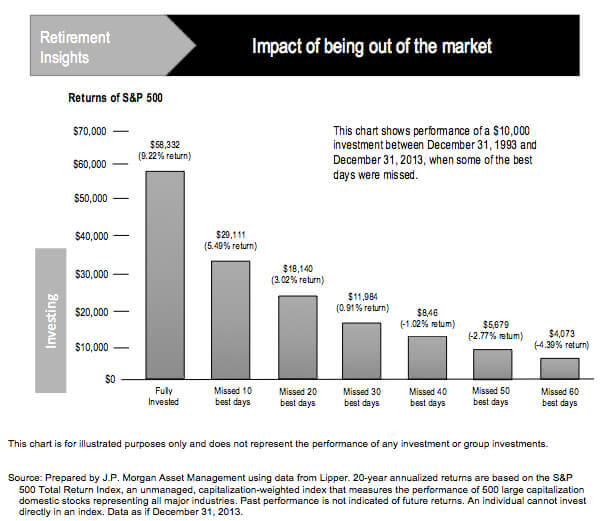

To reinforce this idea, let’s look at some extreme but illustrative examples of how much it could have cost an investor to miss some key days of surging prices.

Let’s take the 20 years from December 31, 1993 to December 31, 2013. The markets were open for more than 5,000 days. If an investor stayed invested through all those days, a $10,000 investment would have multiplied to $58,332.

Now, take out just the best 10 days — less than 1/500 of the total time — and the total value of that portfolio drops to $29,111, wiping out almost exactly half of the returns over 20 long years.

If an investor missed just 40 days, less than 1% of the 20-year time period, that 9.2% average annual gain would get converted into a loss of $854. So patience and staying in for the long term are crucial for investment services. The same reality applies to individual stocks but even more forcefully.

The Cost of Liquidity

Cash drag is another way of looking at the same issue. For example, if you have $10,000 more than you need in a money market account where returns are about 5% less than what you might earn from a long-term investment, then you lose $500 every year you keep it there!

For most individuals, excess liquidity means time out of the market, which history has shown to be a costly mistake.

A more subtle and serious problem with liquidity is the temptation of what’s known as easy action. In other words, if you have the money sitting there and that next big thing comes along you are more likely to buy it impulsively.

America’s favorite investor, Warren Buffett, illustrates the discipline that can substantially improve your decisions on investments with a “decision ticket.” Imagine you have a lifetime ticket that provides you with only 10 decisions to invest. Each time you make an investment decision, one of those 10 numbers gets punched. After 10 punches, you must turn in your card, and for you, it’s game over! You can make no more investment decisions. You’d be particularly diligent and make each of your decisions with great care and self-discipline.*

The Case for Limiting Your Liquidity and Where to Get It

Every long-term investor wants and needs some liquidity in an emergency fund to be prepared for managing the inevitable bumps in the road ahead (see Build the Emergency Fund That’s Right for You). As we discussed in detail in the emergency fund post, you should always have enough cash in liquid, low-risk investments to cover your day-to-day expenses for six months as well as mundane, unexpected events like repairing a leaky roof, your car or the like.

The other important use of liquidity is to make a major planned purchase such as a new home or a child’s college tuition. As you approach a major expenditure, it’s wise to remember that the requisite resources should, over a few years, be accumulated from savings or raised by selling long-term investments and then holding them in a more liquid form, like a money market account.

For larger expenditures, most of us have multiple sources: cash reserves, car or other bank loans, mortgages, stockbroker margin accounts or through selling some securities.

Now, take out just the best 10 days — less than 1/500 of the total time — and the total value of that portfolio drops to $29,111, wiping out almost exactly half of the returns over 20 long years.

Several clients have asked questions related to the purchase of a home. Is it a good idea to buy as an all-cash transaction? Is it better to pay off mortgages early? We think both are generally unwise for a number of reasons, but for our purposes here, we’ll simply say that your money can be put to more productive use by reaping returns in a long-term investment, especially if you can get a reasonably low rate on a mortgage (please see the related sections of Eight Financial Planning Actions You Should Consider for the New Year for a deeper dive).

If you have reason to believe you might want to borrow from your bank, you’d be wise to visit your bank before you need to borrow, and learn how best to arrange such a loan as well as how much and on what terms your bank will lend you money. Poet/humorist Ogden Nash’s genial description of one rule of banking all bankers should follow is an entertaining admonition on the subject:

“…They all observe one rule which woe betides the banker who fails to heed it,

Which is you must never lend any money to anybody unless they don’t need it…”

Again, keep your liquidity within reason through planning and wisely borrowing well within your capacity to pay back on schedule.

These days many investors are making mistakes that behavioral economists increasingly consider predictable. The market may not be the cause of all those costly mistakes, but liquidity is guilty of being an enabler of many of them, as human beings are and want to be active. Try to limit your use of liquidity as history shows extra liquidity has done more harm than good.

About the author(s)

Charles D. Ellis, CFA, PhD, is a member of Wealthfront’s investment advisory board, the author of Winning the Loser’s Game and, with Burton Malkiel, The Elements of Investing. View all posts by Charles D. Ellis