At some point in its evolution, every startup faces the question of whether or not it should partner with a large company to accelerate its growth. On the surface, partnering almost always looks like a great idea. Unfortunately, the reality is seldom as rosy.

Partner Motivation: The Chesbrough Framework

In my experience, understanding your potential corporate partner’s motivations will tell you a lot about how likely it will behave post investment. In my product/market fit class at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, I use Hank Chesbrough’s outstanding framework to describe the motivations that drive corporate partnerships (Hank is a professor at the University of California’s Haas School of Business).

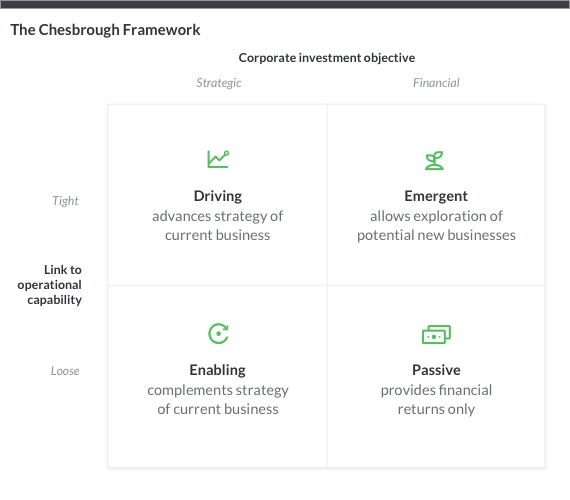

Like most compelling frameworks, it is based on a simple two-by-two matrix: On one dimension the “Motivation for the investment” can either be strategic or financial. On the other the dimension, “Organizational fit” with its current business can either be tight or loose.

Chesbrough refers to a strategic motivation with a tight organizational fit as a “driving” investment because it has the opportunity to drive significantly increased revenue in the corporate partner’s own business. A strategic motivation with a loose organizational fit is called “enabling” because it is motivated by a desire to grow the market it currently serves. Intel investing in companies that build products that require a lot of processing power is a classic enabling investment. A financial motivation and a tight organizational fit is called “emergent” because it might be an opportunity in the future, but is not one today. Corporate partners pursue this kind of investment for its option value because they may be interested in a closer relationship in the future. A financial motivation with a loose organizational fit is called a “passive investment” because it is made purely for financial return.

Look for a Driving Investment

In my experience the only kind of corporate relationship worth pursuing is a driving investment. Corporate partners are far more likely to pay attention to their investments if their portfolio companies help drive a significant increase in their own product revenues. That’s because companies are valued based on their future operating cash flows, which are far more likely to be impacted by a multiple increase in their own product revenues than by selling another company’s products.

I am not a fan of enabling investments because as an entrepreneur I want to be my partner’s passion, not option. A corporate partner who invests in your company purely for the opportunity to see how the market plays out has no motivation to help you. As a startup you face enough challenges that you should only want to involve people who are motivated to help in every possible way.

Emergent investments are not terribly relevant because they are quite rare. If a passive investment is what you’re after, then a venture capital firm is likely to provide more help.

The best recent example of a driving investment was Microsoft’s 2007 investment in Facebook. Prior to the partnership, Microsoft faced significant headwinds in its attempt to sell Bing-based advertisements. In return for a $200 million investment, Microsoft earned the exclusive right to sell Facebook ads. The ability to offer a bundle of Facebook and Bing ads enabled Microsoft to significantly grow its Bing business.

Intel’s 2014 investment of $740 million in Cloudera was a classic example of an enabling investment. The success of big data should drive the need for a lot more processing power and therefore more microprocessors. As mentioned earlier Intel was a pioneer when it came to this kind of investment. Unfortunately, over the past 10 years the vast majority of Intel’s investments have been what Chesbrough would classify as passive, which may explain why they haven’t had much of an impact on Intel’s stock price.

Cisco is the company most associated with emerging investments. It has taken minority positions in scores of companies and followed up with acquisitions when the investees proved they had created important new markets.

Corporate Partners: Who is Driving?

The challenge with a driving investment is that its strategic importance usually leads the corporate investor to attempt to exert influence over the investee to get what it believes is appropriate for the market. Unfortunately, the corporate partner’s view of what’s needed seldom jives with the startup’s perspective. This usually leads to an over specified product, which in turn leads to time to market delays.

Eric Ries and Steve Blank revolutionized the way entrepreneurs think about business in large part by stressing the importance of getting a minimum viable product to market to get the feedback necessary to iterate into the most attractive niche. Corporate partners in the driving quadrant typically are not interested in the “lean startup” approach because they usually have very strong opinions about what they need and don’t think it is necessary to experiment to find product/market fit.

Making a profit on its investment is of little value to a corporate partner because publicly traded stocks are valued based on their future operating cash flows. Investment profits are not considering an operating cash flow, so it seldom impacts the value of the corporate investor’s stock. It only has value if the value of the investment exceeds the value of the corporate investor’s main business, which is very rare (think Yahoo and Alibaba). If the value of the investment is meaningless then the only reason to invest is to improve one’s own business (driving) or get an insight into a business that might hurt you (emergent).

Pundits excoriated Microsoft for investing in Facebook at what seemed like a ridiculously high price ($15 billion valuation), but Microsoft believed that the price it paid didn’t matter. As an investment, it turned out Microsoft made billions, but that had very little impact on its stock price. Microsoft and their investors were far more focused on the improved Bing cash flow that resulted from the deal.

The Innovator’s Dilemma Prevents Successful Partnerships

By now you can see there are some significant issues involved in building an effective corporate relationship even when your goals are aligned. Imagine how much worse it might be if you have a business model that is disruptive to your potential corporate partner. By disruptive I mean the Clayton Christensen definition: a product or service that is uneconomic for the incumbent to address.

According to Christensen there are two types of disruptions: new market disruptions and low end disruptions. New market disruptions address consumers who for one reason or another are not able to buy the incumbent’s product. eBay was a classic new market disruption because Sotheby’s was not able to address people who wanted to sell inexpensive items. A low end disruption is something that is simpler, cheaper or more convenient than the incumbent’s product. Dell sold PCs direct to consumers cheaper than its primary competitor Compaq sold to its resellers. Compaq couldn’t cut its price and go direct because it would infuriate its resellers, on whom it was dependent for billions of dollars of revenue. That would have been suicide for a public company.

A true disruptor creates an innovator’s dilemma (the name of Christensen’s book that introduced the concept of disruption) for the incumbent – attempting to compete with the disruptor will destroy earnings and ignoring the disruptor will allow it to grow and destroy you in the future. Thus the dilemma!

It’s awfully hard for a corporate partner to embrace your product if its investment either hurts its margins or acts as a perceived endorsement that might lead its traditional customers to ask for a lower price.

For this reason, almost every successful Internet entrant chose to compete with the incumbents rather than partner with them. The only exception I know of is the real estate market.

Below is a sample of the ever-growing list of traditional markets that have been destroyed by new Internet entrants:

In each of these cases, partnering with an incumbent would have weakened the new entrant’s ability to position the incumbent as the bad guy who was charging way too much. Imagine Amazon partnering with Barnes & Noble!

I raise the Barnes & Noble issue because Amazon did partner with incumbents after it clearly became the leader. It only chose to work with incumbents like Toys “R” Us once it controlled the power dynamic and was able to dictate the terms of how it wanted to do business. And those terms clearly favored Amazon.

To be fair there are always outliers. As I said before real estate is the one market where the new entrants (Zillow and Trulia) worked with, rather than competed against, the real estate agent community. Trulia is a particularly embarrassing example for me because the two founders, Pete Flint and Sami Inkinen, were my students and advisees at Stanford Graduate School of Business. I strongly recommended Pete and Sami compete with real estate agents rather than work with them based on my 20 years of having observed the incumbent/new entrant dynamic. Fortunately for Pete and Sami they ignored my advice.

Disrupters Look for New Channels

Interestingly, Christensen found that disrupters almost always had to create their own distinct channel for their products. That’s because the typically lower price for a disruptive product leads to far lower margins for the reseller. Existing channels resist taking on new products that have lower margins, which forces the disruptor to find a new channel for which even the low margin is better than what it makes on its other products. Selling via the web or mobile rather than through the incumbent distributor is a classic example of Christensen’s observation.

Don’t confuse partnering to access supply with partnering to gain distribution. Supply partnerships have a much higher chance of succeeding because the private company seldom is interested in disrupting its supplier. Hulu partnered with the networks to gain proprietary access to content in an attempt to disrupt cable operators, the classic distributors of such content. The broadcast networks’ investments in Hulu were driving because they created a new channel for their content.

Startups Should Be Cautious Approaching Partnerships

It’s imperative that you consider to whom you might be disruptive when contemplating a corporate partnership. Chesbrough would argue there’s very little incentive for a potentially disrupted incumbent to make an investment other than one that could be characterized as emerging. Again, that provides no incentive for them to help you.

I faced this dilemma up close. My company, Wealthfront, operates an automated investment service. We employ exchange traded funds (ETFs) from Vanguard as part of our managed portfolio, but we would never take an investment from a firm that offers investment advisory services. Having a potential competitor as an investor weakens the messaging we could use to explain how much they take advantage of their clients with high fees. It also creates the potential for a conflict should we ever want to specifically compete against them. For this reason, venture capitalists are usually the preferred source of private funding because their only motivation is to see the value of your equity grow. They don’t care how you do it and who you irritate in the process. In other words, there are no potential conflicts.

Having a corporate investor could increase your revenues in the short term, based on the credibility it might bring or an initial stocking order. But over the long term the potential impact due to conflicts and delays are likely not to be worth it.

Disclosure

Nothing in this article should be construed as a solicitation or offer, or recommendation, to buy or sell any security. The information provided here is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice.

About the author(s)

Andy Rachleff is Wealthfront's co-founder and Executive Chairman. He serves as a member of the board of trustees and chairman of the endowment investment committee for University of Pennsylvania and as a member of the faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he teaches courses on technology entrepreneurship. Prior to Wealthfront, Andy co-founded and was general partner of Benchmark Capital, where he was responsible for investing in a number of successful companies including Equinix, Juniper Networks, and Opsware. He also spent ten years as a general partner with Merrill, Pickard, Anderson & Eyre (MPAE). Andy earned his BS from University of Pennsylvania and his MBA from Stanford Graduate School of Business. View all posts by Andy Rachleff